The first two of the features above appear

to reduce the risk of surgery, which is especially important when operating

on patients who suffer from morbid obesity. The fact that there is no

cutting or repositioning of any intestine brings the risk of leak or

obstruction to very low levels (not impossible, as outlined in the risks

section below). The fact that the procedure is almost always done

laparoscopically may allow decreased risk on the vital organs (heart, lungs,

etc.) and may allow quicker recovery in comparison to open procedures

"Removable" in the list of key features

refers to the fact that all surgeons experienced with the Lap-Band report

that it can be removed from the patient with little residual impact on the

stomach. These surgeons report that this is even true when the band has

eroded into the stomach, or become infected, or slipped out of position.

This is possible because the silastic substance from which the band is made

creates essentially no tissue reaction, so that the Band is not stuck in

place over time. This feature also means that the Lap-Band procedure is

"reversible" in a certain sense. The Band could be removed because of

medical necessity, and that if it were not replaced by some other weight

loss procedure that the patient would be guaranteed to experience

significant weight regain.

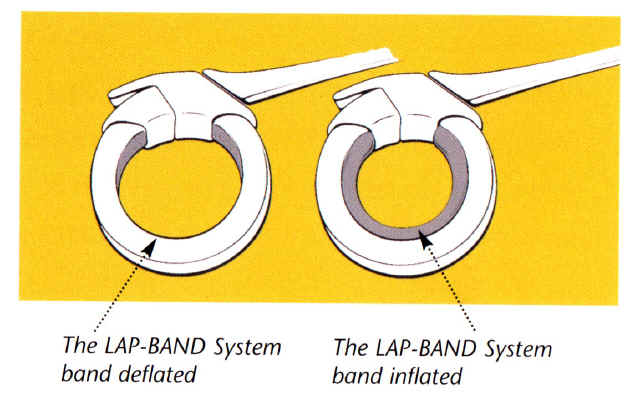

The feature of the Band that deserves the

most attention is that it is adjustable. This is the feature that makes the

Band (in many published reports) successful in helping patients achieve

significant sustained weight loss. After all, if the Lap-Band were not

successful, then the decrease in operative risk would not mean much. The

fact that the Band can be adjusted to help the patient modify their eating

pattern in a way that is specific to that patient is the feature that makes

it different from the failed VBG, which created a fixed/hard restriction on

eating that frequently led to problems over the long haul.

There are several other potential

advantages claimed by advocates of the Lap-Band, which deserve mention.

Slower weight loss - the Lap-Band

aims to create slower and steadier weight loss than the results seen after

most other surgical procedures. Most weight loss operations create very

rapid weight loss in the first few months, which then slows and stabilizes

at 10-18 months after surgery. On the other hand, Lap-Band patients begin

with a relatively loose Band that allows ongoing intake of nutrition, and

the Band is gradually "tightened" according to the patient's weight progress

and satiety symptoms. This approach aims to achieve a weight loss of 1-2

pounds per week, that continues up to or beyond 24 months after surgery.

Lap-Band advocates promote this difference as "gentler" or "safer" or "more

physiologic," but we have frankly seen very few nutritional problems in our

many gastric bypass patients related to rapid weight loss.

Iron, calcium, B12 - operations

that involve rearrangement of the small intestine such as the gastric bypass

or the BPD-DS create a deficiency of absorption of these nutrients. Purely

restrictive procedures such as the Lap-Band should theoretically not cause

such problems because no intestine is bypassed. Caution is needed, however;

almost all VBG patients we see for surgical repair are deficient in Iron

and B12. It may well turn out that the reduction in overall intake is more

important than the specific bowel anatomy. In our practice for the time

being, we are recommending exactly the same supplements after either the

gastric bypass or the Lap-Band.

Open questions The Lap-Band

system has only been in use since the early/mid-1990's, so there is no

long-term data on outcomes. Unbiased observers have raised several

questions about the Lap-Band as outlined below:

Weight loss results & maintenance -

early studies from Europe reported weight loss results that were less

substantial than the Gastric Bypass. However, more recent studies from

Australia (especially from Dr. Paul O'Brien and Dr. George Fielding) have

put out reliable-appearing results in which weight loss after Lap-Band is

essentially equivalent to GBP. The course of weight over many years after

Lap-Band points in the direction of long term maintenance of weight, but the

actual long term results do not yet exist.

Band erosion - all surgeons who

perform the Lap-Band have found erosion of the Band into the patient's

stomach in a small percentage of cases. It appears that this event (which

requires removal of the Band) occurs mainly in the first year or so after

surgery. However the truly long-term incidence of Band erosion remains to

be seen.

Esophageal function - some patients

have experienced failure of normal esophageal peristalsis (swallowing

function) after Lap-Band. If this occurs, it causes painful swallowing,

reflux, or regurgitation. Band deflation or removal is required. More

recent studies suggest that the occurrence of esophageal failure arises from

tightening the Band too aggressively, and that this complication can be

almost completely avoided.

Silastic reaction - it is possible

that the material of the Band could create some type of body immune reaction

that stimulates a separate disease process such as arthritis or Systemic

Lupus Erythematosis (SLE). However the Band is made of a silicone elastomer

which is completely non-reactive to the body tissues, as far as it has been

possible to determine. The same type of material has been in use in a

number of implanted medical devices over time, and no problems with tissue

reaction have been demonstrated. Here again, the early data is reassuring

but no true long-term information exists.

Risks specific to Lap Band

Band erosion - the Band can erode

through the wall of the stomach. This results in loss of restriction to

eating, or Band infection caused by leakage of stomach juices onto the

Band. It is reported that such erosion rarely results in a sudden

life-threatening situation for the patient. Erosion of the Band almost

always requires removal of the Band, with plans for a later conversion to a

different weight loss procedure.

Band slippage or shifting - the

Band must remain in the correct position on the upper stomach in order to

function properly. If it slips out of place or twists, it is likely to

cause obstruction of the stomach, requiring fairly urgent re-operation to

reposition the Band.

Swallowing problems - as mentioned

above, the function of the Band as a partial blockage against outflow from

the stomach pouch may cause the esophagus (which normally pushes food down

in a very coordinated way) to become fatigued or damaged and to fail its

normal swallowing function. The rate of occurrence of this problem varies

widely among published reports, with the more recent studies being more

reassuring.

Hardware breakage - the Band, the

port, and the connection tubing are designed to last for life. In fact, the

Band itself is almost never reported to break or leak. However, the tubing

and the port definitely can become twisted, kinked, or broken. Such events

require re-operations (usually minor) for repair or repositioning of the

problem spot.

Injury to stomach or other nearby organs during surgery - even in

capable hands, the maneuvers involved in placing the Band may sometimes

create injury to the stomach, esophagus, spleen, liver, or to the tissues

involved in placement of the trochars. Sometimes such injuries can be

addressed at the time of surgery and the Band can still be placed.

Sometimes the nature of the injury means it is most reasonable to abandon

the operation.